Covid restrictions have stopped India’s children going to school. In Budhpura, Manjari is bringing school to the children.

It’s no secret that the Covid pandemic has hit India hard. And beyond the news of overwhelmed hospitals, oxygen shortages, and the high death count, are other stories—of the potential long-term impact of this crisis on the country’s children.

Covid and school closures

Last year, over one and a half million elementary and secondary schools in India closed, to try to limit the spread of the virus. A few states began to reopen schools for older children at the end of 2020. However, Manish Singh, secretary of Manjari, the grass-roots NGO that operates in Budhpura, Rajasthan, reports that schools in the area are still closed. The long-term impact—affecting not only the children, but their future families—means reduced earning potential in the years to come.

Varun Sharma is Programmes Director of Aravali, the agency that acts as an interface between the government and grass-roots organisations like Manjari. “With learning levels not good,” he says, “our experts report that it will take another four or five years if you want to fulfill the deficit caused by the long lockdown.”

And that’s if the children return to school. A major challenge has been to keep them interested in learning. In India overall, it was estimated before the crisis that around six million children were not attending school. Now, across the whole country, 247 million children have lost time in the classroom and it is feared that many will never return.

This is partly because some children have returned to work, undoing some of the progress made in eradicating child labour. Absolute poverty is one of the driving factors in the existence of child labour, and no one can blame parents for feeling that, with no school and nothing to do, their children would be better occupied earning money.

Manjari brings school to the children

Again Manjari have been busy, visiting families, explaining that work is not worth the cost to child development—the danger being that work compromises the child’s future as they are not then interested in going back to school.

To an extent, Manjari has become “school”. Although central government set up remote learning initiatives last year, to try to compensate for school closures, the huge urban/rural divide in the availability of the Internet is a major handicap. Pre-Covid, it was estimated that in rural areas only around 4% of households have access. “For the families in Budhpura, having an android-based mobile handset with internet connectivity is still a distant dream,” points out Manish Singh, Secretary of Manjari.

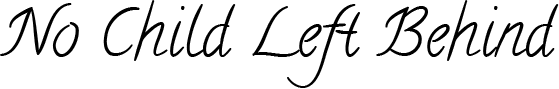

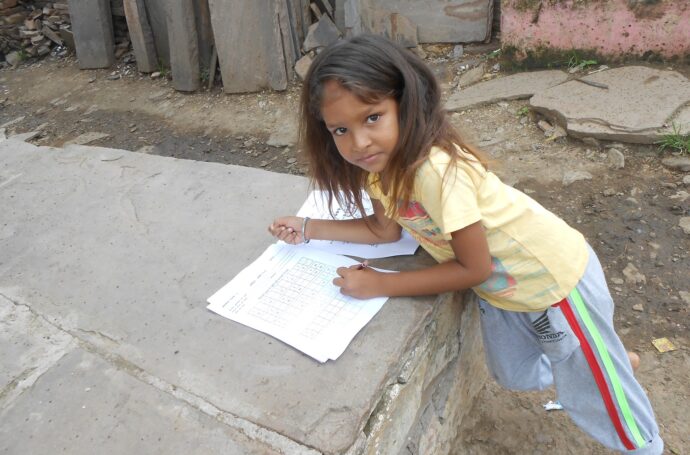

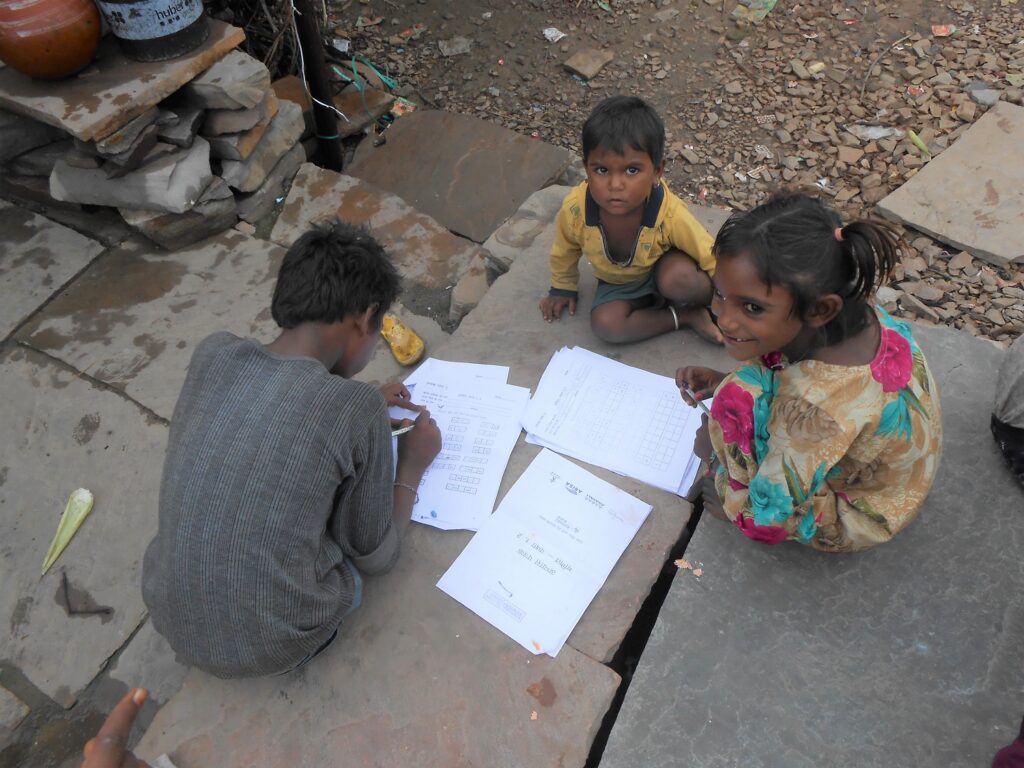

So, when permitted by Covid restrictions, volunteers have brought school to the children. Education Volunteers were briefed and given the responsibility of visiting a hundred households. “We create small groups of children,” says Manish, “and they share worksheets based on minimum academic levels, which come back to us for feedback.” The volunteers have reached around 1000 children in Budhpura and the surrounding villages.

The importance of play

But all work and no play…is never good. “There is also a kind of psychological damage to the growth of children, because their whole environment is restricted now,” says Manish. “So we have distributed sports material to twenty children’s groups. They play in a safe environment with their friends and discuss their tensions.”

The teams have also visited cobble yards, organising games and story-telling nearby so that the children aged two or three years old, who cannot be left at home when their parents go to work, are able to play for an hour or two.

Mobile libraries take books to the children

One of the most successful initiatives in sustaining children’s interest has been the library. Inevitably, because of the pandemic, the central library—which is in Manjari’s office in Budhpura—closed last year. The mobile library was born, transporting up to sixty books at a time to different villages.

Manjari are providing funding and, over the year, the value of this initiative has become obvious. Over 3000 books have been borrowed from the library and there is increasing demand for new ones.

One of the most heartening aspects of working to improve conditions is the relatively small investment needed to make an impact. “Reaching to far-flung mining areas is difficult,” explains Varun, “so a small investment is suggested, to get an electric rickshaw—very low cost—which can reach these areas without involving fuel charges. This will help us to reach out to these children with books and developing their learning habits.”

Lack of science facilities

However, dealing with the problems created by Covid has underlined another lack, not related to the pandemic. “The children have no facilities to study science and maths,” says Manish. “There are no teachers for these subjects, so we are not creating interest in the children. And the ages of nine, ten and eleven are when a child gets their attitude to study.”

The consequence is that children have no option except to study humanities—something which skews the future skills base of the country. “We’re in touch with local consultants,” says Manish. “When Covid is over we want to establish a small room at the centre where children come to see experiments.”

To facilitate this, we at No Child Left Behind will be looking into opportunities to provide books, science kits and other resources to spark an interest in children in these subjects in the early years.

But that is for the future. For now, all efforts are concentrated on keeping children and their families engaged, against the time when Covid restrictions will be a past difficulty, overcome.

Read more about Manjari, the grass-roots organisation in Budhpura, in Celebrating Budhpura! and The NGO helping to eradicate child labour