The pictures were striking. Millions of workers streamed out of cities, setting off to walk hundreds of miles back to their home village, just days and hours ahead of the Indian Government’s lockdown and travel ban to combat the spread of Covid. Writ large in the midst of this exodus in 2020 was the huge impact of having an unregistered workforce.

Registration gives access to social security. Without it, a worker has no state support when times get hard. This is a situation with which Manjari, the NGO that works on the ground in the cobble-producing area of Budhpura, Rajasthan, has been familiar for many years. Whether migrants or locals, the workers are not, for the most part, registered.

Improving labour conditions for all is a vital part of creating Child Labour Free Zones. To this end, Manjari has been involved in discussions with yard owners for many years over the need to register workers so that they can access their employment rights.

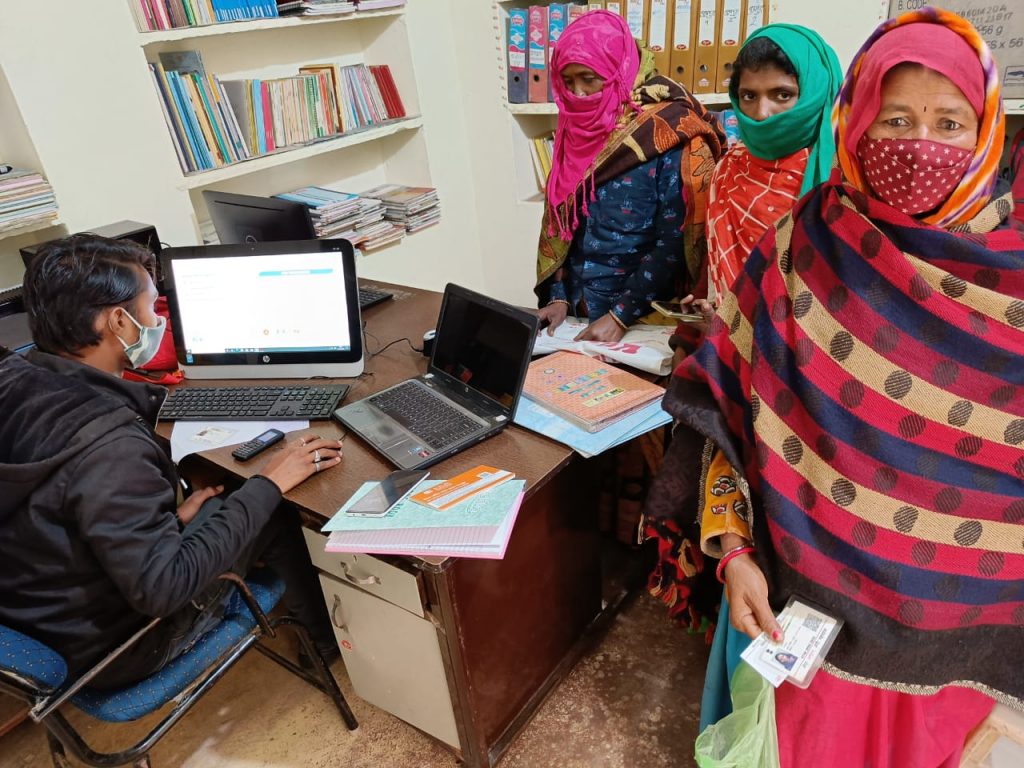

Registering the e-Shramik card

The e-Shramik card—a new Government scheme—has given Manjari a welcome step forward. Set up last year to give each worker a unique 12-digit number, it allows access to employment benefits and social security.

However, for those without the latest digital devices or without access to the internet at all, registration can be difficult. Others have stepped in to fill the gap. “People are trying to get money out of it,” says Manish. “It should cost 20 to 30 rupees, but now they are charging 200 to 300 rupees.”

To help workers, Manjari has established a registration centre with Internet access, a printer and a laminating machine. “We have reached out to women in the self-help groups, for example,” he says, “and in only a few days we made a hundred cards.”

This is interesting work for Manjari, who are seeing workers who have not come forward before. It’s also very intensive. Going door to door in ten villages so far, they have ensured that, in each, every household has one. A new registration camp will shortly be set up in nearby Sukhpura. “We hope to reach all workers in the area,” he adds.

A complication is that the registration needs to be linked to a person’s Aadhaar card—essentially, an identity card that helps with access to banking and mobile phone services, among other things.

“And linking the e-Shram to their employer is very important,” says Manish. “When they get harmed or there are violations at the workplace, we need to know in which workplace they are.”

Working with businesses

Although the e-Shram is a welcome development, it’s only part of the answer. “Local businesses are maintaining their distance,” explains Manish. “Although we’ve been here for 10 to 12 years now, they’re not coming forward.”

This is not to say that much has not been achieved. One yard has an electronic machine which logs on workers via facial recognition or a thumbprint. Workers are increasingly recognising the benefits of formal work practices like this because it gives them a record of the hours they’ve worked. And informal education centres in cobbleyards have resulted in a good number of young children going on to enrol in school.

“We need to develop greater trust between all the stakeholders,” says Manish. “They become defensive. But we are not blaming them for anything, just asking for a little more—for systems that make sure every child is going to school, every worker has their rights.”

The power of positive pressure

This is where companies like London Stone and Brachot, supporters of No Child Left Behind, can add their voice. “We need positive pressure from international companies,” says Manish, “so we can make it clear that there is no harm if every child is going to school, and that having everyone registered in no way impacts the business.”

To that end London Stone and Brachot will be approaching their suppliers to encourage registration. This is something that everyone involved with landscaping can help with, whether you’re having a new garden designed, are designing one, building one, or importing landscaping materials. Show it matters how the materials are produced. “Many companies based in Europe don’t know the details of everyone in their supply chain,” says Manish.

Just start asking questions. And join us in applying positive pressure for change.